Recent cases in Britain of serious disease in horses caused by severe encysted small redworm infections have prompted a veterinarian to remind owners of the risks posed by not treating for the potentially fatal parasite.

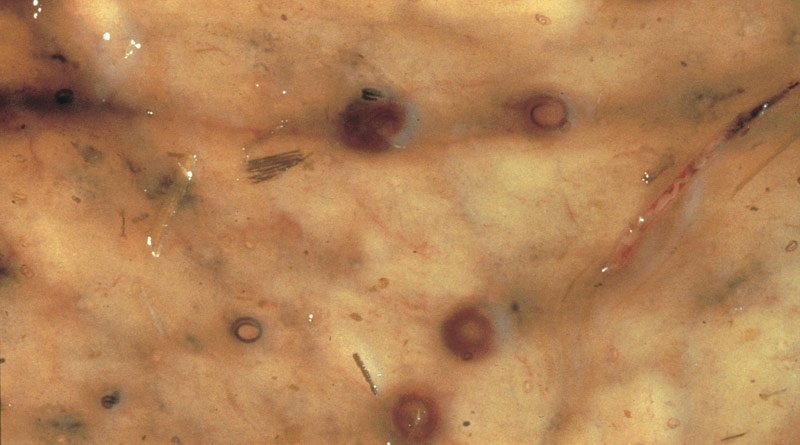

In spring the small redworm larvae can erupt from their hibernation inside the horse’s gut in large numbers, breaking and damaging the lining of the intestinal wall. Symptoms include diarrhoea, weight loss and colic. This condition (known as larval cyathostominosis) can be fatal. Young horses (<6years old) have the highest risk although all ages may be affected.

Unfortunately people think their horses are safe from this parasite if they have had a recent, negative faecal worm egg count (FWEC) but this absolutely is not the case. Because encysted small redworm are hibernating, they won’t show in faecal worm egg counts. A horse could actually have a burden of several million encysted small redworm larvae yet show a negative or low FWEC.

Currently there is no effective test for encysted stages of small redworm. All horses of more than six months of age should be dosed for it ideally during the late autumn/early winter and certainly before the spring arrives.

There are only two active ingredients licensed to treat encysted small redworm: a single dose of moxidectin or a five-day course of fenbendazole. However, there is widespread evidence of resistance in small redworm to fenbendazole, including the five-day dose so a resistance test is recommended before using it. Moxidectin has high efficacy against adult small redworm including encysted mucosal larvae.

It’s vital to use the right worming product, treating with a wormer that does not specifically target the encysted stages (ivermectin, pyrantel or single dose fenbendazole) during late autumn and winter can actually increase the risk of a horse with a high encysted small redworm burden developing larval cyathostominosis.